Jack the Ripper is an alias given to an unidentified serial killer[1] active in the largely impoverished Whitechapel area and adjacent districts of London, England, in late 1888. The name originated in a letter sent to the London Central News Agency by someone claiming to be the murderer.

The victims were women earning income as prostitutes. Two of the victims' throats were cut, after which the bodies were mutilated. Theories suggest that the victims first were strangled, in order to silence them, which may explain the reported lack of blood at the crime scenes. The removal of internal organs from three of the victims led some officials at the time of the murders to propose that the killer possessed anatomical or surgical knowledge.[2]

Newspapers, whose circulation had been growing during this era,[3] bestowed widespread and enduring notoriety on the killer because of the savagery of the attacks and the failure of the police to capture the murderer (they sometimes missed him at the crime scenes by mere minutes).[4][5]

Because the killer's identity has never been confirmed, the legends surrounding the murders have become a combination of genuine historical research, folklore, and pseudohistory. Many authors, historians, and amateur detectives have proposed theories about the identity of the killer and his victims.

Background

In the mid 19th century, England experienced a rapid influx of mainly Irish immigrants, who swelled the populations of both the largely poor English countryside and England's major cities. From 1882, Jewish refugees escaping the pogroms in Tsarist Russia and eastern Europe added to the overcrowding and the already worsening work and housing conditions.[4] London, especially the East End and the civil parish of Whitechapel, became increasingly overcrowded, resulting in the development of a massive economic underclass.[6] This endemic poverty drove many women to prostitution. In October 1888, the London Metropolitan Police estimated that there were 1,200 prostitutes "of very low class" resident in Whitechapel and about 62 brothels.[7] The economic problems were accompanied by a steady rise in social tensions. In 1886–1889, demonstrations by the hungry and unemployed were a regular feature of London policing.[4]

The murders most often attributed to Jack the Ripper occurred in the latter half of 1888, though the series of brutal killings in Whitechapel persisted at least until 1891. A number of the murders involved extremely gruesome acts, such as mutilation and evisceration, which were widely reported in the media. Rumours that the murders were connected intensified in September and October, when a series of media outlets and Scotland Yard received a series of extremely disturbing letters from a writer or writers purporting to take responsibility for some or all of the murders. One letter, received by George Lusk, of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, included a preserved human kidney. Mainly because of the extraordinarily brutal character of the murders, and because of media treatment of the events, the public came increasingly to believe in a single serial killer terrorizing the residents of Whitechapel, nicknamed "Jack the Ripper" after the signature on a postcard received by the Central News Agency. Although the investigation was unable to connect the later killings conclusively to the murders of 1888, the legend of Jack the Ripper solidified.

TopWriting On The Wall

After the murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes during the night of 30 September, police searched the area near the crime scenes in an effort to locate a suspect, witnesses or evidence. At about 3:00 a.m., Constable Alfred Long discovered a bloodstained piece of an apron in the stairwell of a tenement on Goulston Street. The cloth was later confirmed as being a part of the apron worn by Catherine Eddowes. There was writing in white chalk on the wall (or, in some accounts, the door jamb[10]) above where the apron was found. Long reported that it read:

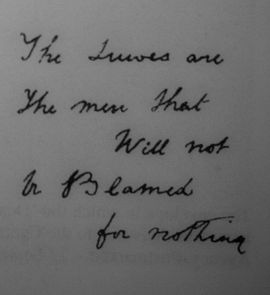

"The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing."

The writing is referred to by a number of authors as the "Goulston Street Graffito".[18][3][22] Detective Daniel Halse (City of London Police), arriving a short time later, took down the following version: "The Juwes are the men that Will not be Blamed for nothing." A 'copy' (according with Long's version) of the message was taken down and attached to a report from Chief Commissioner Sir Charles Warren to the Home Office. Police Superintendent Thomas Arnold visited the scene and saw the writing. Later, in his report of 6 November to the Home Office, he claimed, that with the strong feeling against the Jews already existing, the message might have become the means of causing a riot:

"I beg to report that on the morning of the 30th of September, last my attention was called to some writing on the wall of the entrance to some dwellings No. 108 Goulston Street, Whitechapel which consisted of the following words: 'The Juews are not [the word 'not' being deleted] the men that will not be blamed for nothing,' and knowing in consequence of suspicion having fallen upon a Jew named John Pizer alias 'Leather Apron,' having committed a murder in Hanbury Street a short time previously, a strong feeling existed against the Jews generally, and as the building upon which the writing was found was situated in the midst of a locality inhabited principally by that sect, I was apprehensive that if the writing were left it would be the means of causing a riot and therefore considered it desirable that it should be removed having in view the fact that it was in such a position that it would have been rubbed by persons passing in & out of the building."[23]

Since the Nichols murder, rumours had been circulating in the East End that the killings were the work of a Jew dubbed "Leather Apron." Religious tensions were already high, and there had already been many near-riots. Arnold ordered a man to be standing by with a sponge to erase the writing, while he consulted Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren. Covering it in order to allow time for a photographer to arrive was considered, but Arnold and Warren (who personally attended the scene) considered this to be too dangerous, and Warren later stated he "considered it desirable to obliterate the writing at once."

Police 'copy' of the writing in Goulston Street, attached to Chief Commissioner Sir Charles Warren's report on "the circumstances of the Mitre Square murder."While the Goulston Street Graffito was found in Metropolitan Police territory, the apron piece was from a victim killed in the City of London, which has a separate police force. Some officers disagreed with Arnold and Warren's decision, especially those representing the City of London Police, who thought the writing constituted part of a crime scene and should at least be photographed before being erased, but it was wiped from the wall at approximately 5:30 a.m. Most contemporary police concluded that the text was a semi-literate attack on the area's Jewish population. Several possible explanations have been suggested as to the importance of this possible clue:

According to historian Philip Sugden there are at least three permissible interpretations of this particular clue: "All three are feasible, not one capable of proof." The first is that the writing was not the work of the murderer at all. The apron piece was dropped by the writer, either by accident or design. The second would be to "take the murderer at his word" — a Jew incriminating himself and his people. The third interpretation was, according to Sugden, the one most favoured at the Scotland Yard and by "Old Jewry": The chalk message was a deliberate subterfuge, designed to incriminate the Jews and throw the police off the track of the real murderer.[24]

"But suppose the killer happened to throw the apron, quite fortuitously, down by the existing piece of graffiti? In such a case we would be utterly wrong in according to the writing any significance whatsoever. Walter Dew was inclined to endorse this approach to the problem. (...) Constable Halse, on the other hand, saw it and thought it looked recent. And Chief Inspector Henry Moore and Sir Robert Anderson are both on record as having explicitly stated their belief that the message was written by the murderer."[25]

Author Martin Fido notes that the writing included a double negative, a common feature of Cockney speech. He suggests that the writing might be translated into standard English as "The Jews are men who will not take responsibility for anything" and that the message was written by someone who believed he or she had been wronged by one of the many Jewish merchants or tradesmen in the area. A contemporaneous explanation was offered by Robert Donston Stephenson (20 April 1841 – 9 October 1916), a journalist and writer known to be interested in the occult and black magic. In an article (signed 'One Who Thinks He Knows') in the Pall Mall Gazette of 1 December 1888, Stephenson concluded from the overall sentence construction, the double negative, the double designation "the Juwes are the men," and the highly unusual misspelling that the Ripper most probably was of French-speaking origin.[26] This claim was disputed by a native French speaker in a letter to the editor of that same publication that ran on 6 December.[27] Author Stephen Knight suggested that "Juwes" referred not to "Jews," but to Jubela, Jubelo and Jubelum, the three killers of Hiram Abiff, a semi-legendary figure in Freemasonry, and furthermore, that the message was written by the killer (or killers) as part of a Masonic plot.[28] There is, however, no evidence that anyone prior to Knight had ever referred to those three figures by the term "Juwes."

TopVictims of Jack The Ripper

These are the Ripper's victims that most experts agree on:

Suspects

Many theories about the identity and profession of Jack the Ripper have been advanced. None have been entirely persuasive, though there have been many theories based on the letters sent to the Central News Office. Some have encompassed the theory of a young man who was heavily influenced by Jack Sheppard, a burglar who died in 1724, who read pennydreadfuls. Other clues from letters sent determined that the writers of the most convincing letters were written by a man of the lower class, with only a rudimentary education.

Top